Airborne

Ena Selimović

Embroidery: Ena Selimović

It is our nature to have more admiration for the things above us than for those that are on our level, or below.

René Descartes, “Of the Nature of Terrestrial Bodies”

tr. Paul J. Olscamp

In March 1999, the US and NATO launched a joint military action called “Operation Allied Force” in the newly dissected Yugoslav region. On the surface, the mission was humanitarian, aimed to stop Slobodan Milošević’s genocidal campaign against Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, but there was a different story in the air.

The word “zrak,” meaning “air” in Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian (BCMS), contains the word “rak,” meaning cancer. You grow up knowing air—invisible and everywhere—can be fatal. You learn the word “pomoć,” meaning “help,” and see “moć,” meaning “power.” Air contains cancer, help contains power. When you hear “I live to serve others” or “I did it for my country,” you recall that help, like power, is also self-serving, that self-help is just power with a market.

In February 1998, your parents arrive to the United States as refugees with two young children. Your father, a fighter pilot newly hired at the freshly merged Smurfit-Stone containerboard factory, grows thinner devouring English words,* rewriting sentences that describe new needs:

Pitam se da li biste mi mogli pomoći.

I wonder if you could help me.

Next to the verb “moći” (to be able to), he adds what he takes to be synonyms, words meaning “to know”; “to want to”; “to have the capacity to”; “to be in a position to.” The unwritten sentences include:

He knows how to fly a MiG-21.

He wants to fly.

He has the capacity.

But:

He is in no position to.

Mounting paperwork—not to mention containerboard—attests to a reality he will never see in black and white. According to Serbian documents, he is a Bosnian Muslim. According to Bosnian documents, he is a traitor. According to Turkish documents, he is a spy. According to American documents, he is an alien. According to them all, he is to be put in no position to help others or himself.

* Your mother grows thinner with your father, and even thinner from your father, but what follows is primarily a narrative about men in fighter jets.

Chief of Staff of the US Air Force, General Michael E. Ryan, declared that the Air War Over Serbia (AWOS) would “help the Air Force decide its future direction based on an examination of the first major war in history fought exclusively with airpower.” Operation Commander General Wesley Clark—Supreme Allied Commander, Europe (SACEUR) for NATO—“doubted that an air campaign could ever succeed without an accompanying ground campaign,” recalling the Soviet Union occupation of Afghanistan and the US occupation of Kuwait.

Unlike General Ryan, General Michael E. Short, who served as Ryan’s Combined Force Air Component Commander (CFACC), “wanted to hit Belgrade as hard as Baghdad had been hit in 1991.” In a Frontline interview, Short cited what he’d learned from Viet Nam as a major influence in how he wanted to direct air operations against Serbia—and indeed, diffractive missile and stealth technologies were first developed to target MiG-21s flown in Viet Nam:

You remember in southeast Asia, for years we bombed a little bit, and then we backed off. […] Then finally we sent the B52s north around January of 1973, and lo and behold, we brought them to the table. Now that is certainly a simplified version from a now-old fighter pilot. But in a then-young fighter pilot’s mind, my generation learned that you take the fight to the enemy. You go after the head of the snake, put a dagger in the heart of the adversary, and you bring to bear all the force that you have at your command.

He added, regretfully, “We weren’t able to go for the head of the snake that first night [in Belgrade].” General Clark had overridden Short’s proposal.

Short knows how to go for the head of the snake.

He wants to.

He has the capacity.

But:

He is in no position to.

A lady who sings in a church chorus that meets in the building your mother cleans offers to give your ten-year-old you piano lessons at a reduced rate after noting your preference for quietly admiring the grand piano in Fellowship Hall over vacuuming felošipov—as you come to know it. Practice makes perfect, your piano teacher tells you, and in your spiral notebook, you rewrite the lyrics accompanying the notes to track “00” on your newly acquired Casio CTK471:

I can open your eyes

Take you wonder by wonder

Over, sideways, and under

On a magic carpet ride

You practice for what turns out to be a less-than-perfect New Year’s Eve, when your parents and your Yugoslav-Bosnian-Muslim-German-alien friend’s parents ask you to perform a duet of “A Whole New World,”* with you on the keys (accompaniment ON) and her Irish dancing. A difficult position to be put in.

* The parents don’t actually request the song by name, which—you learn much later, and learn to laugh about still later—is a signature song from Disney’s 1992 feature film Aladdin.

The United Nations’ “Report of the Secretary-General prepared pursuant to resolutions 1160 (1998) and 1199 (1998) of the Security Council,” published in October 1998, outlines the motivations behind Operation Allied Force. Paragraph 9 of the report begins:

I am outraged by reports of mass killings of civilians in Kosovo, which recall the atrocities committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina. [...] Most were children and women at ages ranging from 18 months to 95 years.

This is how the first line reads in the French translation of the document:

Je suis indigné par les informations faisant état de massacres de civils au Kosovo, qui rappellent les atrocités commises en Bosnie-Herzégovine.

In Russian:

Я возмущен сообщениями o массовых убийствах гражданскиx лиц в Косово, вызывающий в памяти зверства, совершенные в Боснии и Герцеговинe.

Paragraph 24 of the report begins:

Although aid agencies have significantly expanded their operations in Kosovo, total requirements are not being met because of the restrictive environment in which aid agencies operate. The security operations have continued to delay relief convoys travelling to populations in need until they have deemed an area “secure,” have carried out protracted shelling of targets in close proximity to large groups of internally displaced persons and have displayed extremely heavy-handed behaviour when dealing with displaced persons.

In Arabic it reads:

In his blue hardbound notebook, your father writes:

I am flying

– above clouds

– in and out of clouds

– continuously in clouds

– in the clouds

– between two layers of cloudsI am avoiding clouds.

Asked about his “most vivid memory of the first night” of air operations over Serbia, General Short recalled the US pilots’ response after shooting down three MiGs: “There’s an old American beer commercial that says, ‘After the work day is over, it’s Miller time.’ That was the code word—the young men liked it. So when everybody was out, the strike commander made the call that it was Miller time.”

When the operation was completed, the nations involved had a soirée: “The Spanish flew in a large tray of paella,” Short explained, “and we had beers from different countries, and just kind of let off some steam. It was just a bunch of airmen walking around saying, ‘Hey, we got it done. Nobody died. We didn’t lose any kids.’”

Among those kids was his son, serving in the squadron directed to identify Serb military targets in Kosovo. To ensure safe voyage, his father—General Short—limited how low the aircraft could fly before dropping munitions. The chosen number was 15,000 feet. At such an elevation, Short knew the probability of mistaking civilians for enemy targets was high: “Under the limitations I had placed on the crew to stay above 15,000 feet and to let the forward air controllers go down to 10,000 feet for excursions, it was inevitable that we were going to drop a bad bomb.” He was referencing a sortie in which his son mistook a tractor pulling a wagon for two armored trucks. The rules were updated thereafter.

At the end of each month, your piano teacher gives your mother a handwritten invoice:

March 3 $15

March 10 $15

March 17 $15

March 24 $15

Her cursive handwriting makes each “15” look like the tangled power cord of a vacuum.

“You go after the head of the snake, put a dagger in the heart of the adversary, and you bring to bear all the force that you have at your command.”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines snake as: “One or other of the limbless vertebrates constituting the reptilian order Ophidia (characterized by a greatly elongated body, tapering tail, and smooth scaly integument), some species of which are noted for their venomous properties; an ophidian, a serpent.” The entry for “to snake” reads: “To skulk or sneak.”

Even as commanders disagreed on overall approach, much of the air power for Operation Allied Force was supplied and applied by the US, which had its own name for the campaign: “Operation Noble Anvil.” Of 38,004 sorties, the US Air Force completed some 30,000 sorties and supplied some 400 aircraft—all but two of which, lost in a training accident, “returned safely during 78 days of around-the-clock-operations.”

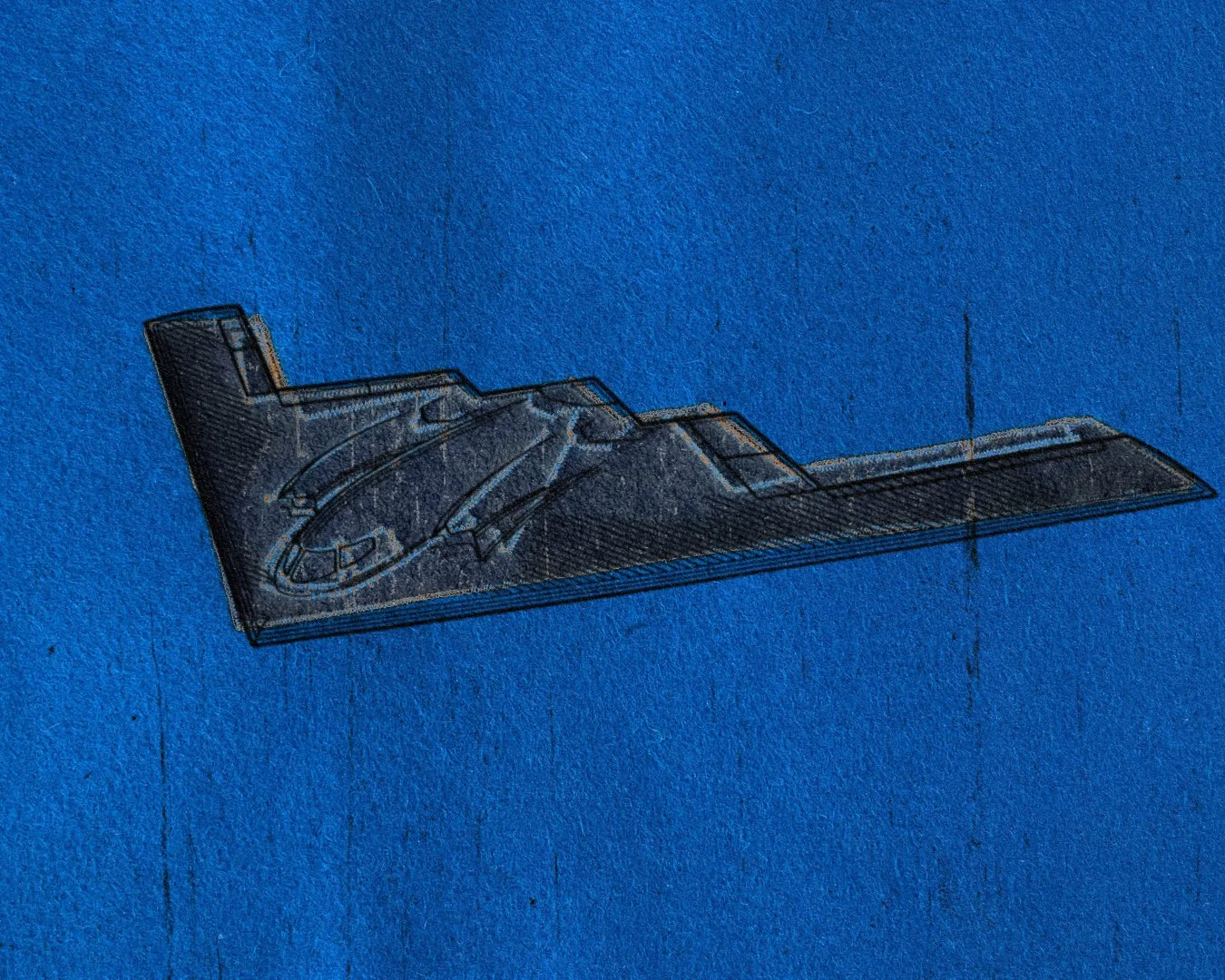

The supply included six B-2 stealth bombers, which took flight for their first combat test, just shy of a decade after Northrop Grumman Corporation’s B-2 design patent application was approved. The bombers flew from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri to Serbia, a 29-hour roundtrip journey, and flew over 300 sorties. Even the B-2 pilots had “concerns about being able to continue the long Missouri-Yugoslavia round-trips beyond a couple of weeks,” writes John A. Tirpak in “With Stealth in the Balkans.” But in hindsight, they found “they could have kept up the bombing campaign as long as necessary.”

On a Wednesday in June 1999, the congressional Military Procurement Subcommittee met to discuss the B-2 bombers’ performance in Kosovo and Serbia. General Leroy Barnidge, Commander of the 509th Bomb Wing based at Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, explained the B-2 pilots’ capacity to expertly manage fatigue:

We in the bomber world have learned the value of what we call power naps. These are short naps which are intended to refresh you, but not long enough to where you get into deep sleep, which then requires an extended recovery period to come out of. Because of the importance of this issue, fatigue management, I asked every crew after they landed, how do you feel and how much sleep did you get? They all said they felt good and all said that they got between 2 and 6 hours of sleep, in small increments, of course, and of course only one guy at a time; and perhaps more significantly, all asked when could they go again.

California Representative and Subcommittee Chairman Duncan Hunter called on Washington Representative Norman Dicks of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee to speak. Dicks was introduced as “a great champion of the B–2” and declared, “Stealth truly saves lives.” Dicks continued, “The B–2 pilots all returned home safely. In fact, one pilot confided to me that the first time he went to Whiteman Air Force Base, when he returned from his 31-hour mission, his wife said, ‘Honey, take a nap, but when you get up, you’ve got to mow the lawn.’”

Although longer than leadership hoped, Operation Allied Force, in Haulman’s words, “demonstrated that nations determined to use airpower effectively in the name of humanity could stop genocide.” But Major General Bentley B. Rayburn argued that the campaign’s “most notable and distinct accomplishment was not that Slobadon [sic] Milosevic finally withdrew his forces from Kosovo, but rather that air and space power prevailed despite senior leaders’ reluctance to take major risks and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization alliance held together.” So who’s to know?

In 1999 Missouri, your father clips newspaper ads with the words:

JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! EMPLOYMENT SERVICE: EAGLE JET INT’L. GUARANTEED INTERVIEWS AND JOB PLACEMENT WITH AIR CARRIERS TO QUALIFIED EAGLE GRADUATES!

and

LAND A DREAM JOB. LITERALLY. PILOTS: ACCELERATE YOUR CAREER WITH NORTHWEST AIRLINK, THE NATION’S FASTEST GROWING REGIONAL AIRLINE.

He circles the words “Scholarship Plans Available.”

In 1965, engineer John Cashen was awarded a scholarship to leave Bell Labs in New Jersey and become a Hughes Fellow at Hughes Aircraft Company in California. He accepted the opportunity because “the wife of the day, whom I was married to 30 years, was a gal from New Jersey. One, she wanted to go to California; two, given the choice, she’d rather go to Southern California; third, she didn’t want me to be a full-time student. She wanted to start to have a family, and she wanted me to start making money, and continue to make serious money. So I became a Hughes fellow.”

Eight years later, he joined a neighboring company called Northrop Grumman Corporation, where he became principal designer of the B-2 stealth bomber.*

*Soviet engineer Piotr Ufimtsev developed the Physical Theory of Diffraction (PTD) and published his findings in an unclassified electromagnetics journal in the early 1960s. Cashen explains that Northrop’s contract to “calculate the radar cross section of airplanes, using the University of Michigan method, was an Air Force contract out of Wright Field, which gave them the privilege to ask for foreign technology division translations of foreign papers. This is before machine translation. So Dr. Ken Mitzner, who was one of the five great radar cross section engineers who were at Northrop when I arrived—and a Hughes fellow, I might add—ordered that, and he got the translation. He saw the benefits of this and in the ’60s started to use it as part of the development of the GENSCAT hierarchy of computer codes, and to publish PTD articles.”

An Army Air Forces ad in the May 15, 1944 issue of LIFE magazine reads: “Every young man who wants to fly can today find exceptional opportunities for improving himself. . . Don’t neglect any opportunity to prepare yourself in mind and body for better service to your nation, your community, and yourself.”

Practice—!—makes perfect.

As of 2025, nineteen B-2 bombers are in operation and all are based at Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri. With an average cost of two billion US dollars per unit, twenty-one stealth bombers were manufactured, and two lost to malfunctions. After Yugoslavia, the bombers flew to Afghanistan (2001), Iraq (2003), and Libya (2011, 2017). In June 2025, seven B-2 stealth bombers traveled continuously for 37 hours from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri to Iran and back. A “likely target,” Chris Gordon wrote in Air and Space Forces Magazine, was Iran’s Fordow nuclear enrichment facility, an attack that would “likely be executed by multiple B-2s carrying 30,000-pound GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrators, enormous bunker-busting bombs designed for deeply buried targets.” It was the first operational use of the 30,000-pound weapons.

We share the air. Nothing happens in a vacuum.

A Yugoslav-Bosnian-Muslim refugee to the US who works, first, in a factory making containerboard and, finally, before hanging himself, as a long-haul truck driver, your father comes home from the road and what does he do? He mows the lawn, and then he takes a power nap.